About

After Empire

By Christopher Y. Lew

In his wide ranging 2019 book, How to Hide an Empire, historian Daniel Immerwahr charts how American imperialism eschewed past models of conquest and the US, instead, created a network of small -scale territories and military bases that dotted the globe, without a large colonial enterprise and primarily out of the eyes of its citizens. Certainly, the white settler land grab is very much part of US history, especially throughout the course of the 19th Century when Indigenous land was brutally taken in the name of progress and westward expansion. So much of the violence, exploitation, and extralegal maneuverings of this period would serve as the foundation for an American version of empire—one in which so-called territories are a grey area in US law and, subsequently through advancements in communications and logistics technologies, those bases can be far from one another and no longer required traditional colonial structures to support them. In effect, most mainlanders had little knowledge of the very people that constituted the country in its entirety—that by 1940, 12.6% of the US population did not live in the contiguous states.¹

Santiago Bose, who can be regarded as the grandfather of Filipino contemporary art, grew up in amid the physical manifestations of this American empire. Born just after World War II, in 1949 in Baguio City, he grew up in a city that was built from scratch in the early 1900s by the US occupation, originally as a summer retreat for the white colonizers complete with “large government buildings, commanding views, a grand axis cutting through the Baguio meadow.”² Growing up in this built environment in the 1960s, Bose was first exposed to rock ‘n’ roll as well as American and European art through the nearby American military bases. Though as his biographer Jonathan Best relates, Bose’s memories of his youth “soured as he grew older and came to feel Filipinos were being treated like second-class citizens in their own country when they visited the American bases.”³

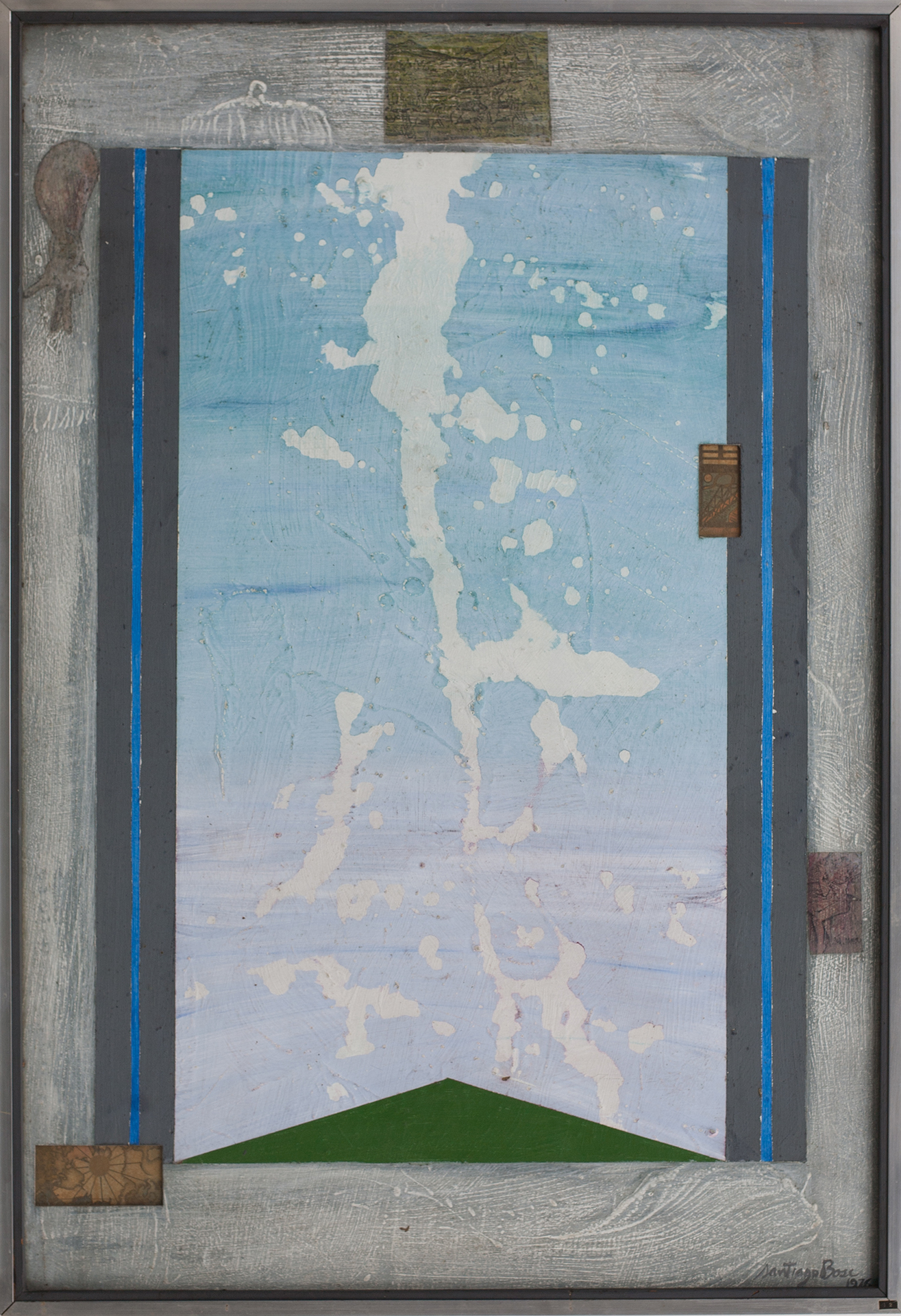

In Bose’s assemblage, Baguio Souvenirs (1976), the composition is bisected horizontally with an off-white band running across the top and a thin, desaturated red below, to resemble the corridors of an administrative building. Embedded into the “wall” are turn-of-the-century surveyor photographs of his hometown. Acting like windows looking out onto the landscape, the appropriated pictures were taken at a commanding height, depicting orderly rows of buildings along wide streets and green fields divided in to crisp geometries by intersecting roads. While they are actual photographs of a real place, they are also a colonizer’s fantasy—a landscape that is organized and pacified, largely devoid of any people. With a trickster’s wit, Bose appropriates the very images initially used to survey and control the land and have them speak back, against the legacy of imperial might.

Stephanie Syjuco’s early three-channel video Body Double (Platoon/Apocalypse Now/Hamburger Hill) (2007) makes use an entirely different set of source imagery which, like Bose, she turns back on itself. Looking at the three titular Hollywood films about the Vietnam War, Syjuco excises the sections of footage that solely depict foliage and landscape, devoid of humans. Sections of jungle appear and disappear in regular, silent geometries—a rectangular sliver of blurry greenery, a square close-up of grass, a wide shot of the sun piercing the canopy overhead. The three movies were shot in the Philippines to stand in for Vietnam (hence the body double), in a sense producing a colonial ouroboros. Syjuco says, “The irony of this—the restaging of an entirely different war being shot in a tropical-like environment of an ex-American colony (the Philippines having been under American colonial rule from 1898 to 1946)—was not lost on me as a Filipinx American artist interested in the construction and fabrication of history.”⁴

By working with marble sourced from the Danby Quarry in Vermont—that largest underground quarry in the world—Michael Joo sets notions of location along an expansive geologic timeline. His Epi- (Montclair Mariposa Cross-Cut) (2024) features a wide slab of marble held up on a steel truss as if it were a roadside billboard. The verso of the slab is coated with silver nitrate—a material used to mirror surfaces and is a precursor to silver compounds used in black-and-white photography—which leaks through the cracks along the face of the stone. The sculpture suggests an inchoate mirror or photograph, charged with the potential for reflection or depicting a captured image without ever doing so. Writing about a related 2014–15 sculpture, art historian Miwon Kwon said: “The work does not offer a surrogate view (of another place, another scene, a feeling or thought, imagined or real) and at the same time does not affirm the position of the viewing subject in the space of the presentation.”⁵ Through its horizontal format, Epi- suggests a view of a landscape without ever providing one and likewise its silvering yields no reflection to satisfy the viewer.

Set in this sequence, these works of Bose, Syjuco, and Joo demonstrate a series of refusals. Bose adeptly renders the tools of oppression inoperable, and by incorporating them into his art, he makes visible the apparatus of colonialism itself. Through deliberate deletion, Syjuco looks to the moving image and its systems of distribution to show how they reinforce nationalist fantasies. Joo’s sculpture is devoid of representation. Informed by the work of Bose and Syjuco, the work takes on an anti-colonialist stance, and through its very being it counters the idea of a landscapes ripe for conquest and instead reinforces a notion of tectonic history, a timeline that extends forwards and backwards beyond any human timeframe and any kind of nationalistic mythmaking.

¹ Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire (New York: Picador 2019), 11.

² ibid, 130.

³ Jonathan Best, “Childhood Roots of a Baguio Artist”in Espiritu Santi: The Strange Life and Even Stranger Legacy of Santiago Bose (Makati City: Water Dragon, 2004), 40.

⁴ Charles Mudede, “The Cinema of the Block Universe in Stephanie Syjuco‘s Body Double (Platoon)” in e-flux Film, June 21-27, 2021, https://www.e-flux.com/film/402557/body-double-platoon/

⁵ Miwon Kwon, “Silver Interference: Michael Joo’s Theory of Reflection” in Michael Joo, exh. cat. (London: Blain|Southern, 2016), 8.

Santiago Bose (1949–2002, Baguio City, Philippines) was a mixed-media artist, educator, community organizer and art theorist. Co-founder of the Baguio Arts Guild, he is recognized as a pioneer in the use of indigenous materials. His influential assemblages champion the resilience of indigenous cultures within the context of a society inundated with foreign influence. As a widely sought-after artist for public commissions and artist residencies, Bose’s practice included extensive international travel and several prominent grants and fellowships. In 1976, Bose was granted the Thirteen Artists Award by the Cultural Center of the Philippines. He has participated in major international exhibitions, including the Third Asian Art Show in Fukuoka, Japan, and the Havana Biennial in Cuba, both held in 1989.

Employing diverse media and materials, Korean American artist Michael Joo (b. 1966, New York, USA, lives and works in New York) draws together creative and scientific modes in innovative conceptual work that reflects on the intersection between technology, perception, and the natural environment. Joo’s materials are as diverse as his body of research, ranging from human sweat, silver nitrate, and bamboo. Major exhibitions include Perspectives: Michael Joo, Smithsonian Freer | Sackler Museum, Washington, DC, USA; 49th Venice Biennale, Korean Pavilion, Italy; Sensory Meridian, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL, USA; Michael Joo, Conserving Momentum (Egg/Gyro/Laundry Room), White Cube London, UK; Michael Joo: Drift, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT, USA; Michael Joo: Drift (Bronx), The Bronx Museum of Arts, New York, NY, USA; Michael Joo, Doppelganger, Cass Sculpture Foundation, Sussex, UK; and Michael Joo Retrospective, Palm Beach Institute of Contemporary Art, Palm Beach, CA, USA.

Stephanie Syjuco (b. 1974, Manila, Philippines; lives and works in Oakland, CA) is celebrated for her interdisciplinary practice encompassing photography, sculpture, and installation. Her work employs open-source systems, shareware logic, and capital flows to scrutinize issues related to economies and empire. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Smithsonian American Art Museum. A long-time educator, she is an Associate Professor in Sculpture at the University of California, Berkeley.

Installation views

Works

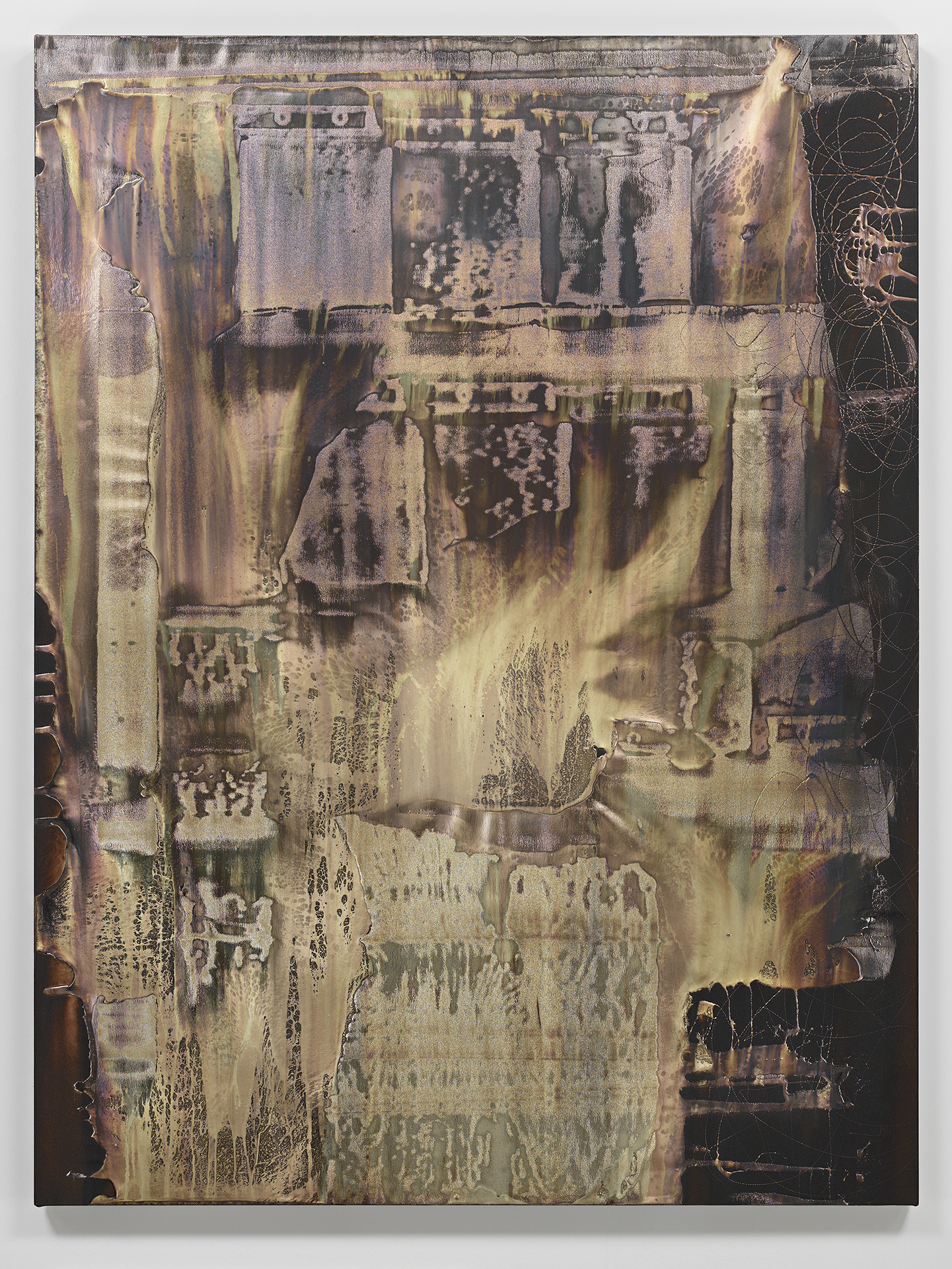

In this series of surprising paintings, Joo coats canvases with silver nitrate and situates them in abandoned architectural ruins. Over several days, a chemical process transposes an image of the surfaces onto the silver-coated canvas. The result is an abstracted imprint of place—a fragile, frozen moment that captures the intersection of time, material, and process. This particular work was created in the long abandoned New York City Farm Colony. Active from 1898-1975, the Farm Colony was a site of indentured servitude that housed people in need and debtors in exchange for farm work. It later doubled as a retirement community.

Writing about a related 2014–15 sculpture, art historian Miwon Kwon said: “The work does not offer a surrogate view (of another place, another scene, a feeling or thought, imagined or real) and at the same time does not affirm the position of the viewing subject in the space of the presentation.” Through its horizontal format, Epi- suggests a view of a landscape without ever providing one and likewise its silvering yields no reflection to satisfy the viewer.

In this series of surprising paintings, Joo coats canvases with silver nitrate and situates them in abandoned architectural ruins. Over several days, a chemical process transposes an image of the surfaces onto the silver-coated canvas. The result is an abstracted imprint of place—a fragile, frozen moment that captures the intersection of time, material, and process. This particular work was imprinted from the site of a derelict factory in Red Hook, New York, once used to produce parts for ships.

Syjuco says, “The irony of this—the restaging of an entirely different war being shot in a tropical-like environment of an ex-American colony (the Philippines having been under American colonial rule from 1898 to 1946)—was not lost on me as a Filipinx American artist interested in the construction and fabrication of history.”

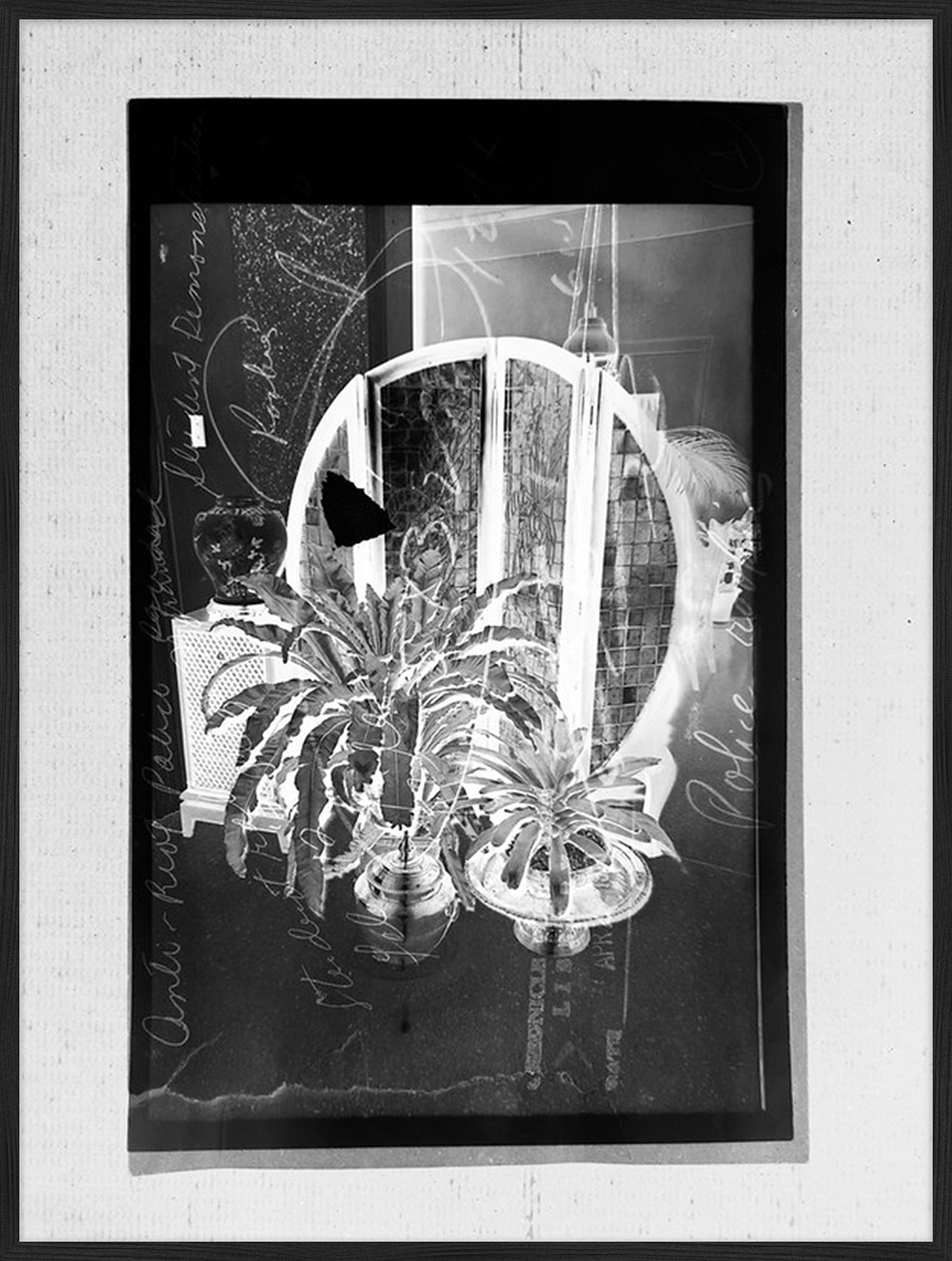

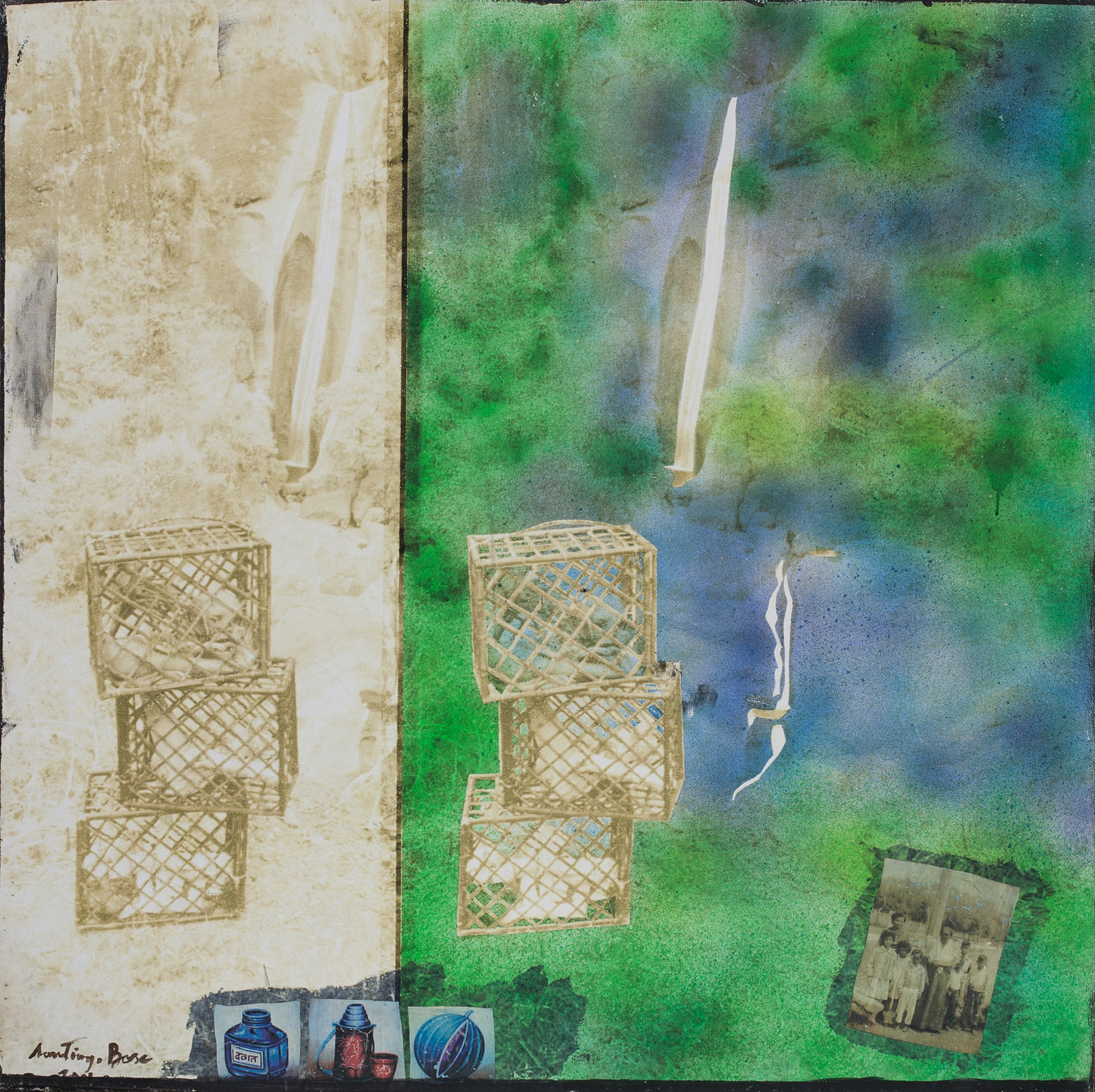

In the final years of his life, Bose continued the Travelling Bones series with a group of paintings incorporating photo transfers from the documentary images he personally captured of the Bones journeying through the Philippine landscape. Preoccupied by his own mortality, he combined these images with old photographs from his youth.

In the final years of his life, Bose continued the Travelling Bones series with a group of paintings incorporating photo transfers from the documentary images he personally captured of the Bones journeying through the Philippine landscape. Preoccupied by his own mortality, he combined these images with old photographs from his youth.

In the final years of his life, Bose continued the Travelling Bones series with a group of paintings incorporating photo transfers from the documentary images he personally captured of the Bones journeying through the Philippine landscape. Preoccupied by his own mortality, he combined these images with old photographs from his youth.